Chapter 1

Sunrise flitted through the simple drapes, falling on MaryAnn’s sleeping form. Unwilling to meet the morning just yet, she turned away but sighed into her pillow. She knew she had to rise and get ready for the day. Morning mass was in an hour.

Sitting up, she rubbed sleep from her eyes and slid out of her humble cot. Going to the standing mirror, Mary’s lips flattened at how wan her skin looked in her pale nightshift. Her blonde hair had a dull sheen and her eyes were rimmed by dark half-moons. If anyone looked closely, they would see that she was worried—but Mary hoped no one would ask why.

Turning from the mirror, she glanced through the shuttered casement out to the rolling land of Saint Albans. The forest beyond was dotted with humble cottages and windmills, which made her smile. It was so peaceful.

Looking over her shoulder, MaryAnn glanced over at her dear friend Ashley Bingley, daughter of Baron Hammond. She held in a laugh. Ashley was wrapped up in the covers with not even a hair peeking out. It was fair to say her friend was not willing to rise that morning.

Going to edge of the bed, Mary gently shook the lump she assumed was Ashely’s shoulder. “It’s time to wake, Ashley,” she shook her again. “We’ll be late for mass and breakfast if you don’t rise quickly.”

The more she shook Ashley, the more the younger miss refused to respond, and Mary grew exasperated. “Sister Agnes will not be pleased at us being late again.”

At the threat of displeasing the oldest and strictest nun at the convent school, finally, Ashley tugged the covers down and levelled a glare at MaryAnn. “That’s not nice of you.”

“But it got you up, did it not?” Mary smiled apologetically as she went to the wash-closet. “We needn’t cause more trouble. We’ve been late to breakfast and mass three times this month. I would not like to be tardy a fourth time.”

Grumbling under her breath, Ashley shucked off the covers and went to wash. In a quarter of an hour, both were dressed in the grey habit all the girls wore in the convent, with their hair plaited and tucked behind their ears with pins.

When MaryAnne opened the door, Sister Claire, one of the youngest nuns, stood there in the corridor, her hand lifted to knock.

“Good morning, girls,” Sister Claire said affably, her smile wide and comforting. “I hope you’ve had a good night?”

Bobbing out curtsies, MaryAnn replied, “Yes, Sister Claire.”

“And you, dear Ashley?” the nun asked.

With her face hinting red, Ashley stammered, “It was . . . erm . . . well enough.”

“Well, come along, it’s time for breakfast,” Sister Claire said, turning round, the hem of her black habit fluttering against the floor.

Following the sister, they headed down the wood-lined corridors, past the other rooms where girls were already seated for a day of reading. This hall was for girls MaryAnn’s age, ten-and-seven or ten-and-eight, in their majority and ready for their debuts into Society.

Their parents—just like MaryAnn’s—had sent them to the convent to grow up humble, with good manners, and all the graces ladies of the ton would need. But MaryAnn also felt girls were sent to the convent school to delay their transition to Society. She knew her parents were afraid that launching her into the ton too early would tempt her to stray from God and become spoiled and selfish.

Her parents needn’t have worried, as MaryAnn was sure that instead of going back to London, she wanted to be a nun—but she did not have the nerve to tell them yet. It was why her worry had begun to show on her face.

They descended the narrow stairs and headed to the dining hall, a long, rectangular room with lengthy trestle tables set with simple placemats, dishes, and cups. The scent of porridge and flaky brown bread met MaryAnn’s nose.

Silently they took their places and bowed their heads for the blessing. She followed the Latin prayer easily and solemnly joined the rest of the girls with the Amen. Taking her bowl, she joined the line to the serving table and received her porridge and bread.

Going back to her seat, she tucked into her meal, while looking at Ashley and hiding a smile. Her friend still looked half-asleep, and MaryAnn could wager that her friend would drift off during mass. Sister Claire was at the head of the table, and MaryAnn was to her direct right.

“So, dear,” Sister Claire said. “I cannot believe you are going to be eighteen in a matter of days. It seems only yesterday you came here at eight summers. Have you decided what to do?”

Holding back a grimace at hearing the very question she so much wanted not to be asked, MaryAnn’s thoughts fell on her parents, who were set to visit that Sunday after mass.

“I have decided what to do, Sister Claire,” MaryAnn replied. “But I would prefer to speak about it with my parents first. I hope you understand.”

“Of course, MaryAnn,” Sister Claire smiled genially.

“I’ll tell you on my birthday,” MaryAnn tried to smile but it fell flat. “I promise.”

“Please don’t fret about it,” Sister Claire said as she finished her meal. “It’s time for mass, please wash up and return.”

“Yes, Sister Claire.”

* * *

Kneeling with her head down, MaryAnn looked around St. Albans Cathedral; the vast building lay within walking distance from their school. The ornate candlestick holders on the altar glistened and reflected the light from the wall sconces as the priest intoned the holy Advent prayers.

MaryAnn kept her head bowed as though in prayer, but her brown eyes dropped to her lap. They’d all been kneeling for at least an hour, and she knew she must continue to do so as the Latin service carried on. She, as well as everyone else, intoned the twelfth—or was it thirteenth? —amen of the Mass, and the hairs on the back of her neck stood up. She had the strongest feeling that someone was watching her, and with a cursory look she found Sister Agnes’ rheumy blue eyes on her.

Dropping her gaze, MaryAnn went back to wondering how she would tell her parents that a life back in London was not for her. Ladies of the ton had an image they must maintain at all times, a constant stream of new dresses, and a similar constant pull to attend social engagements, balls, luncheons, musicales, what-have-you that Mary found frivolous. Moreover, the role of a lady was more ornamental than anything else, and she didn’t believe they put stock in education at all. With her profound stores of knowledge, they might see her as an anomaly.

She took in a breath and decided that the best way would be to tell her mother first.

When the priest called for the Lord’s Prayer, she joined the congregation and recited it, and after a lifetime of recitation, she didn’t have to search hard for the words. Instead, her attention returned to how to tell her parents about her decision to become a nun.

With mass finally over, she worked her way through the mass of people leaving the chapel, attempting to be as unobtrusive as possible. She never understood why people liked to mingle when Mass ended; the only thing she craved was to finish her lessons and escape to the garden with her whittling knife.

The nuns came and called the girls to order, and, in two neat lines, they processed out of the chapel and back to the school. Heading into the lane leading up the hill to the school, she distracted herself by declining French verbs and thinking about what she would do when she came to her lesson in needlework.

She tried every possible distraction to not think on how her father would react when he learned she did not want to marry. MaryAnn trudged up the hill, her heart still sinking; knowing that she, as the only child of a prosperous baron, and a lady at that, had a duty to marry so the line could continue.

Arriving at the main hall of the convent school, she headed to her room to slip out of her heavier shoes and into kid slippers. Ashley trailed in, the lethargy lifting from her face.

With humor, MaryAnn asked, “Are you awake now?” Ashley flashed her a skeptical smile, as if to say, “What do you think?”

After reaching for her pencils and paper, MaryAnn headed off to her first lesson with a laugh in her heart and a jaunt in her step.

* * *

“Is that all, Sister Marie?” MaryAnn asked, while shutting the last of the lesson books into a wooden cabinet. The shelves were filled with several volumes of light literature, poetry, biography, travels, and history. Once or twice, MaryAnn had found a few romances there, but they were soon gone—not that it mattered anyhow, she was not one for fancy.

“Yes, dear,” the elderly woman nodded, “That is all, you can retire to your pastime, but heed the call for supper.”

Glad to escape, MaryAnn left the schoolroom and headed to her room to quickly sweep, tidy her belongings, and then she went out to the garden. She stopped at the gardening shed and plucked out her whittling knife before hunting for the discarded hunks of wood she knew would be scattered through the grass.

She was sure the school helpers would have chopped wood for their weekly fires, study rooms, and cooking. After sifting through the grass, MaryAnn found a hunk of wood that made her smile in satisfaction. Taking it, she found one of the wrought-iron benches scattered around the garden and sat.

For a moment, she considered what to carve. She had made a dozen birds, over two-score of critters, and more flowers than she could count.

Staring at the wood, she considered an idea she’d had a few times—what about making a puppet? Something human-like—a little boy perhaps? Putting knife to wood, she begun to shave little slivers off, bit by bit. It calmed her, gave her an odd peace, and for once she felt in control of her life. The nuns had routines, and she followed them to the best of her ability, but even then she fell short at times. Carving gave her a sense of command.

Soon, she had the basic figure of a boy in her hand, and she was shaping the head when someone sat by her. From the corner of her eye, she saw Ashley and greeted her. “How were your lessons?”

Instead of answering directly, Ashely peered at the figure in MaryAnn’s hand. “What is that?”

“I’m trying my hand at making a puppet,” MaryAnn replied while lifting her other hand to brush back an errant tendril of hair from her eyes. Twisting the wood in her hands, she hummed. “Not too bad, is it?”

Shaking her head, Ashley laughed, “I do believe you might be the oddest lady in England. But I do applaud your uniqueness.” She then pulled something out from her apron. “This just arrived for you. It is from your family, I believe.”

Dropping the carving and knife on her lap, MaryAnn took the letter with a smile. “Thank you.”

“You’re welcome,” Ashely smiled, her blue eyes much brighter now than they had been earlier that morning. As she stood to head back towards the building, she added, “Don’t be late for supper. A little bird told me we will be getting Shepherd’s pie tonight, your favorite.”

“I won’t,” MaryAnn replied while looking at her letter. She saw her name scribbled in her father’s bold handwriting and felt the nerves she had valiantly tried to hold at bay resurge in her chest.

Opening it, she paused before reading, hoping and praying her father had not already made plans for her debut into the ton. Then, she forced her eyes open. A line in, she breathed in relief—no plans for the debut, but there were lines on how she was missed at home.

“You mother and I dearly miss you, and we cannot believe that you will be ten-and-eight in a matter of days,” MaryAnn read to the wind whistling through the leaves around her. “You will not have to stay at the convent school much longer, as your mother and I have decided that your education is complete . . .”

Her eyes darted over the letter, and she picked up a few lines that made her worry even more. I am very excited to have you home, as you are our only daughter, and you’ve been away from so long, we want to spend all our time with you.

She swallowed, “Spend all your time with me . . . before what?”

Studying in the convent was important for our family legacy and your own social and educational upbringing, otherwise I would have kept you home with an army of governesses.

“Your mother and I will be coming to the convent tomorrow to speak with you. We love you, darling,” she read with her stomach twisting anew.

Dropping the letter, she stared at the salutation at the end, signed with his name, title, and seal. While her father’s words were genial and loving, she felt they were vague and grew more worried about why her parents were coming to meet her. The prospect of returning home, of being away from her friend, and the comfort of the convent began to siphon the happiness from her heart.

Staring at the half-formed wooden shape in her hand, she could only whisper a prayer: “Dear Lord, please hear my request, I only ask that things will work out in my favor. That I will not be forced to go back to where I do not feel I truly belong, and that my parents will not force me to leave the one comfort I have, please, Lord, let it be. I cannot imagine anything else.”

Chapter 2

Twilight was Adam Russel’s worst enemy; the shifting light, the haze between dark and light, and the dancing shadows made his poor eyesight even more troubling than normal. The youngest Duke of Bedford pressed his palms to his eyes and let out a long, slow breath.

The journey to Northampton was starting to take its toll on him, and even worse, the reason he had undertaken such a long journey had proved futile. Pulling his hands away from his eyes, he blinked away the black spots that sometimes peppered his vision when he was exhausted and breathed in relief when the window on his right side came into focus.

The healer promised me she could help me . . . but she couldn’t.

“Healing waters of the ancient spring, she said,” he murmured vacantly to himself while watching the trees pass by. “Why in heavens name did I believe her?”

Under all the pain and frustration, Adam knew why—desperation. Since his situation had started to deteriorate, he had searched far and wide for any help he could find. Now, with all resources almost depleted, he had started clutching at straws.

The countryside was slipping by, and he lifted his hand to knock once on the roof of his lacquered carriage. “Where are we?”

“St. Albans, Your Grace,” the driver, Crawford, replied. “About two hours from London.”

Suddenly, Adam felt fatigued and knew he could not stand any more travelling that evening. Casting around in his mind, he tried to remember if there was a posting inn nearby where he could rest for the night.

“Is there an inn nearby, Crawford?” he asked, running a hand across the back of his neck and wincing at the tension resting there. “Any place where we can stay the night? I feel dreadfully fatigued.”

“I fear not, Your Grace,” the driver replied. “But there is a cathedral and a convent just up the road. Less than a mile, I believe.”

“Head there, please, Crawford,” Adam directed him. “I cannot stand making the rest of the journey now, and I think it’s best for you and the horses to get some rest as well. We’ve been on the road for a long while.”

“Yes, Your Grace,” his faithful servant replied and snapped the reins.

Settling back into his seat, Adam tried not to think of what he would be forced to do when he got to London. He would have to put his steward in charge and then find a suitable relative to take charge of his dukedom.

At six-and-twenty, he knew he should have already been married and had an heir or two, but he had not put much energy into courting and finding a wife. Balls and social soirees made him uncomfortable, and his skin itched to go home and find a delightful book to read before his fire with a glass of sherry in hand. Very unfit for a duke, but that was how he was, self-contained.

Truthfully, the ladies I met were as shallow as the cups they drank their tea from.

Not once had he met a lady of substance. One who was kind, thoughtful, and truly intelligent. Once, he had asked a lady her opinion on the Le Traite du Paris, and she had blinked her wide blue eyes twice and asked if that were a new sort of French fashion.

Well, there is Miss Hatfield.

Sighing, Adam shied away from thinking of her. Despondent, his head slipped to the side, and he started to doze, his thoughts chasing each other. It was only when the carriage jerked to a stop that he was shaken from his lethargy. He looked out to see wide stone steps and large oak double doors, bookended by two tall stone columns. He realized they had arrived at the convent.

“We’re here, Your Grace,” Crawford announced.

With a nod, Adam eased himself out of the seat and mounted the steps. Night was swiftly falling, and he felt fatigued to his bones. A brisk wind buffeted him, and he gritted his teeth against the cold while he rapped quickly but loudly on the door with his cane.

Another icy breeze skittered over him, and he hear the rumbling of thunder in the far east—was a storm coming in? If so, they would need shelter. As he lifted his hand to knock again, the grate of a bolt being pulled back and a latch lifted caused him to step away. The door opened, and a nun lifted a candle high.

“May I help you, sir?”

Adam bowed, “Good evening, I am sorry to disturb you, but I am Adam Russel, Duke of Bedford, and I kindly ask if you have rooms for me and my coachman to stay this night. We’ve been traveling a long while, and I thought it best for us to rest instead of pushing on in our fatigue.”

The nun’s eyes widened. “Of course, Your Grace, it will be our pleasure to help. Please, come in. I’ll have one of our hands show your coachman to the stables, and then I’ll conduct him to his room as well.”

“One moment,” Adam nodded, then went to tell Crawford the arrangements before darting back up the steps.

The nun introduced herself as Sister Claire, and he smiled, “Thank you, Sister. I know this is a little out of the ordinary.”

“It is our holy vocation to look out for others in need,” Sister Claire said, ushering Adam inside. “Please, come. I will need to speak to Reverend Mother Agnes Tilbery, but I am sure we can give you a bed for the night.”

She led him to a wide hallway that emptied into a large hall where Adam barely made out the edges of trestle tables and chairs. He focused on the tiny light from the candle and surreptitiously felt his way along so he did not bump into anything.

Sister Claire led him up a flight of stairs to an eerily silent hallway, but Adam did not mind; without the presence of his Scottish deerhounds, the convent would not be that different from his townhome in the outskirts of Mayfair.

She came to a door and knocked, and when the person inside said, “Come,” Sister Claire went in. He dawdled at the doorway and heard snippets of the conversation between Sister Claire and a woman he assumed must be the abbess.

He stepped away when Sister Claire stepped out, and a lady, old, wizened, and dressed in thick robe and woolen cap, came to the doorway. This time Adam bowed, “Reverend Mother.”

When he straightened, he met a pair of bright, blue eyes that leveled an assessing look at him, “You are welcome here, Your Grace. Our house is always a haven for the weary traveler.”

“Thank you,” he replied. “I and my driver appreciate it your hospitality.”

After a few parting words, Sister Claire led him to another level, where, judging by the number of doors, the rooms seemed to be set further apart than in the Abbess’s corridor below.

As he opened the door, he was greeted by a surprisingly well-appointed room. The bed was large enough to accommodate him. It was clean and the linens looked fresh. There was wood stacked near the fireplace ready to be chucked into the grate, but that was all—and Adam found he did not mind the starkness.

He did not miss the brocade hangings around his bed nor the Aubusson carpet at his feet. The simple curtain fluttering at the window was more than enough.

Turning to Sister Clair he nodded, “Thank you, this will be more than comfortable, Sister.”

She bowed her head, “Our pleasure, Your Grace, and your companion will be settled in soon as well. Please know that this convent is also a school for young ladies and some might be about. May the Lord be with you this night.

“Thank you,” he replied, while wondering if the nun had been subtly warning him to not engage with any of the students. She needn’t worry, he had no interest in anything or anyone but regaining his sight.

After she closed the door between them, Adam tugged off his jacket and slid a finger under the knot of his cravat to loosen it. It felt as if it were strangling him. Doing away with both cravat and jacket, he went to the window and braced his hands on the sill. He looked down into what seemed to be a flowering garden.

A sweet and subtle scent lifted from the beds beyond; as his mother had once kept a garden he was familiar with the scent of musk rose and eglantine. He smiled. This place had a sense of peace, of comfort and rest. Turning to the bed, he felt exhaustion flare up again, and he tugged off his Wellington boots before doing away with his cufflinks, then folded his shirt over the back of a chair. Then he tucked himself into bed.

* * *

Heat . . . boiling heat, the fierceness of it searing under his skin. Peeling his eyes open, Adam found himself standing in the middle of a vast stretch of golden sand. The heat beating down on him made everything before his eyes shimmer and glisten.

Dazed, he turned around to determine where he was but saw only endless stretches of sand before him, all of it desert. Not a tree nor a bush nor spring in sight.

The heat was punishing, and he dropped to his knees under the assault, crying out, “Help! Please, someone, anyone, help!”

Even though he continued to cry out, no one came, and he managed to struggle to his feet and begin walking. His feet felt heavy, as if he they were weighted down with irons, but he plodded forward. The sun was harsh and pushed him down, blistering his skin, and soon his legs became fixed where he stood, and he was unable to move.

When Adam looked down, he realized his body was turning into liquid, seeping into the sand—he was melting. Just as he opened his mouth to scream, darkness descended and a chilling, icy, horrendous fear expanded in his chest.

Adam woke with a shout—the dreadful noise echoing around the room, and he shivered under the coat of cold sweat on his skin. Hunching into himself, he covered his face with both hands, fighting to rid himself of the memories of the dream, but failing. His sheet was stuck to his skin, a sickening feel that had him rushing to the window. Flinging the wooden panes open, he gulped in fresh air.

Resting his feverish head on the cool wood and stone, he whispered, “It was just a night terror, only a bad dream. It is not real, not real at all. Nothing is wrong.”

Peeling himself away from the window, Adam woodenly took a few tottering steps and slumped into the chair. His breath had evened out, and the furious pounding of his heart had begun to slow. But his mind was whirling.

He knew it was probably nothing, but could the dream have any meaning? Why had his body melted? What about the desert? Rubbing his face, Adam decided it meant nothing more than a delirious manifestation of the pressure and fear he felt as his eyesight kept slipping away from him.

That is it; the dream means nothing.

Gradually, his chest stopped heaving. But while his eyes lingered on the bed, he could not fathom the idea of going back there. He knew from past experience that even though his body was still tired, he would not sleep. Sighing, he heaved himself up and went to the window again, gazing out at the swaying bushes and spotting a bench almost half-hidden under low hanging tree-branches. He decided to slip outside.

Donning his discarded shirt, he rolled up the sleeves and headed out the door, closing it softly behind him. He did not know the layout of the convent, but he knew there must be a backdoor somewhere.

Reaching the lower level, he searched and found a door with an unfastened latch. Peering at it, he wondered if the nuns had not checked the door, or if someone had slipped out shortly before him. Pulling the door open, he walked through it, and a sigh of comfort left his lips at the cool air that flickered over his face.

It was dark. His eyes strained to differentiate the shifting shadows from the swaying bushes, but he made it to the bench he’d seen from his room and sat. Tilting his head back, he stared at the gibbous moon and the twinkling stars and wished that a sign would drop from the heavens to show him the way . . . and then, the cold steel of knife was pressed to his throat.

Chapter 3

After tossing and turning for hours, MaryAnn had lain in bed, unable to sleep, the worry about telling her parents that she intended to remain in the convent had her thoughts whirling in an unending circle.

She had woken in the middle if the night and looked over at Ashely, who was out like a candle’s wick. Feeling overwhelmed and knowing that sleep would likely elude her for the rest of the night, she dared to slip out of bed and don a thick house robe. She took with her the puppet she had nearly finished, pocketed the carving knife, then she gently eased the door open.

She took care to quietly pad down the hallway and down to the doors below leading out into the garden. She headed to the main one, where a statue of the Virgin Mary stood, and she came to rest on the bench before it. If there was ever a time when she needed guidance, it was then.

Taking the wooden figure out, she began to carve, taking care not to nick her fingers, as the moonlight was very fleeting. “Gentle Mother, how beautiful and sweet you are. Your light is everywhere . . .” Her voice dropped with the prayer and so did her motions with the wooden figure and knife. Instead, she shook her head and said, “I need your guidance on a matter that is keeping sleep from me. I know my parents will ask me to go back home with them, but I deeply feel that my true home is here, in the convent. How do I tell them that without them getting angry?”

A rustling in the trees barely masked the tread of footsteps heading her way. Scared that one of the groundsmen would discover her, she darted away from the seat and hid in the bushes nearby, terrified that someone had seen her.

I will be punished for sure.

As she made up her apology to Mother Superior, she realized the groundsman she had expected to see—was not one at all. Instead, it was a man she’d never seen before. She studied him covertly. The man’s hair was the shade of darkened wheat, the clipped locks gleaming around his handsome, chiseled features. He sat back on the bench and tilted his head up to the stars.

He was not one of the groundsmen, no, his bearing was noble, and the fine fit of his clothes provided another inkling that he was an unfamiliar stranger. She had initially feared that he would report her to Sister Claire. Or worse, Mother Superior, if he saw her, but why would he when he was a stranger?

But—who was he? Unwilling to take any chances, she edged closer, coming up silently behind him and resting her whittling knife at the side of his throat. Her eyes darted to the hastily dropped carved wooden figure now laying a tuft of grass, then looked back at the man, who had frozen in place.

“Who are you?” she demanded in a fierce whisper.

He did not reply, but from the slight movement of the knife, she felt that he had taken a nervous swallow. Inching the blade

a little closer, MaryAnn demanded again, “Who are you? Tell me now.”

Slowly, he lifted his arms, “I come in peace. I mean no harm. My name is Adam Russell, Duke of Bedford. I’ve been travelling for a long while, heading to London, but I felt fatigued, and the gracious Abbess has given me a room for the night.”

Alarmed and horrified at threatening a Duke, MaryAnn yanked the blade away from his neck and felt her palms go cold and clammy. The skin on the back of her neck prickled, and when she moved her legs felt wooden.

Coming around the bench, she swallowed, “I apologize, Your Grace, I did not mean to—ah!”

Swiftly, he had grabbed the knife from her, tugged her to the bench, and held the same weapon to her throat. His blue eyes were glimmering in the low light, and he dropped his tone, sounding dark and sinister, as he held her fast. “I lied. I am no duke but a common thief, intent on robbing this abbey of all its valuables.”

Stunned, MaryAnn found her chest heaving in fright and indecision. Her lips opened once or twice as if to speak, but then they closed. He began to laugh and dropped the knife. He stroked his thumb over the back of her hand, “I’m jesting.”

“You are not a thief?”

“No,” he said, while twisting the knife in his hand and handing her the handle. “I truly am a duke.”

The tension in her back fled, and MaryAnn’s shoulders slumped as she took the knife. Fingering the wrapped handle, she reiterated, “I truly am sorry for trying to threaten you.”

He shrugged. “It is understandable. Anyone would have done the same. May I have your name, Miss . . .”

“MaryAnn Hills,” she replied, unwilling to add her birthright and status.

“And what are you doing out here at this time of night, Miss Hills?” the duke asked quietly.

Turning from him to rest her back on the bench, she looked down. Thinking about her parents’ impending visit and the ball of worry lodged in her chest, MaryAnn simply replied, “I couldn’t sleep and needed some fresh air.”

He nodded sagely. “I found myself in the same situation.”

It was dim, but her eyes could trace the contours of his face, touching first on his jaw dusted with stubble, then up to the taut planes of his cheekbones and thin blade of his nose. Her heart lurched, a hard unexpected wallop against her breastbone, at seeing his thickly-lashed blue eyes framed by dark, strong brows. Brushed with moonlight, she thought he had the most handsome countenance.

Misgivings skittered through her, heightening her sense of disorientation. Who was this man, truly? Should she trust him, or fear him?

Adam twisted toward her. “I assume you are one of the family here?”

“I am.”

One of his brows arched to his hairline. “Are you allowed to talk with strange men?”

Confused by this sudden turn and the odd question, MaryAnn cocked her head to the side, “What you mean by that, Your Grace? Why should I not be able to speak with you, or any man?”

“Are not nuns forbidden to speak to men?” he asked. “I’ve always believed that is a part of the ordinance.”

Amused, MaryAnn shook her head, “You are mistaken, Your Grace. Nuns practice in persona Maria, that is to say they consider the imitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary an integral part of their vocation. They are obedient to the Church and vow obedience for life to the Holy Rule and to the abbess. There is nothing to say we cannot speak to men, unless the nun takes a vow of silence.”

He was silent for a while. “Does that mean you are not a nun but a pupil here?”

“Yes,” she replied.

“And you’re a gentleman’s daughter, correct?” he prodded.

MaryAnn’s cheeks warmed at his correct guess, “Yes. I am the Earl of Chesterfield’s daughter. I have been at this school since I was eleven years old.”

He nodded, “That is a long time. Surely, you must miss your home?”

“That is a delicate matter,” she replied while tilting her head to stare at the stars. “I do miss my home and my parents, but I have grown to love it here at the convent school as well. The nuns and other girls are like a second family to me.”

“You wouldn’t like to leave, then,” he surmised.

“No, I wouldn’t,” MaryAnn admitted. “I’ve come to believe that everything away from this place is only a mirage of kindness, a façade. Unkindness and cruelty are everywhere. I have heard stories about ladies of the ton, horrible sorts who will stop at nothing to get what they want. They are the most cutthroat of all and would stab you in the back whilst smiling and sipping tea.”

Adam’s head snapped to hers, and his lips parted. After a long moment, he chuckled and looked away. “Oddly, that is the most precise description I have heard of some of the ladies. But you must understand, past these four walls it is not all gloom and destruction. There are good people in the world, I assure you. If you go home or get the chance to travel, you will likely meet wonderful people.”

“I disagree, Your Grace.” She shook her head. “I feel perfectly safe, protected, and comfortable here. I cannot think of anywhere else I would rather be . . .” Hesitantly, she scuffed her shoe on a tuft of grass. “My parents are coming to see me on the morrow, and I believe they will ask me to return with them.”

“And you do not want to leave?” he asked.

Unable to speak past the lump that had suddenly formed in her throat, MaryAnn shook her head. The very notion made her feel ill to her stomach, not only because she would lose her friends and makeshift family, but because entering the ton would put her right in the sights of lords who wanted to marry a titled young lady like herself.

“From my own experience, it will be best if you follow your heart,” Adam replied quietly. “If you listen to what your soul tells you, you will not have any regrets or doubts.”

Clarity dawned on her; he was right. God would rest the right decision on her heart, and she would follow it, no matter how frightening it might seem. Turning to him, MaryAnn rested a hand on his, and he turned to her. “You’re right, thank you.”

Adam’s smile was brief, but she caught it, and he bowed his head. Retracting her hand, MaryAnn worried her bottom lip before she asked, “How was your journey? The one that brought you here?”

His head snapped to the side, and his lips pressed tight. MaryAnn even saw the faint tic of a muscle jumping in his cheek and wondered if he were clenching his jaw. A sinking feel settled in her chest, and she realized that her innocent question had touched on a tender nerve.

As she began to apologize and tell him that he did not have to reply, he said, “I didn’t get what I had hoped to, but perhaps that will end up being the best thing for me.”

His words were cryptic, but MaryAnn did not push the matter. Standing up, she said, “I must go back inside now, but I wish you a good night.”

He looked up and the moonlight danced over his hair, rendering the dark, curly locks she had thought were ink-black to a light brown. Adam smiled. “Sleep well.”

She headed to the door but turned to look at him while standing on the stoop. His still, solitary pose wrought an oddly resonant pang in her breast. Almost hidden against the starry night sky he looked . . . so alone, as if he carried the weight of the world upon his broad shoulders.

What is troubling you, Duke of Bedford?

Unable to linger any longer, she slipped inside, leaving the latch open for him whenever he decided to return. Heading to her room, she took a deep breath and wondered if she would ever see him again. The chances were, by morning, he would be gone.

Closing the door and looking on Ashley’s slumbering form, MaryAnn went back to her bed and slid under the blanket, then said a small prayer for the Duke of Bedford. “Good Lord, I ask you that, while I face my troubles, you will heal the pain His Grace, the Duke of Bedford, carries. And if by your sight and mercies you see fit that we should meet again, I hope he will be much happier.”

Chapter 4

Waking with the dawn, Mary’s mind flew back to the Duke of Bedford and the pain she had sensed in his voice. He had felt unrest—why else would he have ventured to the garden in the middle of the night? He was carrying a burden, one she hoped and prayed would be lifted from his shoulders.

Slipping out of bed, she was surprised to see that Ashley was already gone. That was for the best, as MaryAnn wanted to spend some time thinking about last night. She had not seen much of the Duke of Bedford, solely his shoulder and face, and wondered if he were tall and lean of hip, built like a medieval knight from the tales she had read about.

A frightening heat ran up her chest at the memory of his handsome appearance, and she felt an odd flutter in her belly. It was strange, this pull towards a man she hardly knew, but she could not help but think of him. He had not shared much—well, anything, truly—about his life, and she wondered if his problems were related to his family.

MaryAnn washed, dressed, and headed to the dining hall to have her breakfast, all the while telling herself that the Duke of Bedford most likely had already left.

I wish I could have spoken with him again, if only once more. However, this is how it is supposed to be. God makes no mistakes.

Entering the room, she spotted Sister Claire at the head of her table, and after meeting her eyes and smiling a greeting, went off to get her meal. Joining the sister at the table, MaryAnn greeted her. “Good morning, Sister Claire.”

The older woman smiled while reaching for her teacup. “Same to you, MaryAnn. How was your night?”

MaryAnn would have liked to discuss the happenings of last night, but she erred on the side of caution. “I had a peaceful night.”

“Good, good.” Sister Claire nodded while straightening her headpiece.

MaryAnn tucked into her breakfast, cutting up the coddled eggs and wondering about the Duke of Bedford. He had left—she was sure of it, but she wondered if there was any chance they would meet again. She spoke sparingly, and Sister Claire must have realized MaryAnn was not in the mood for conversation because she soon left MaryAnn to her thoughts.

When the morning meal was over, MaryAnn realized there was some time before mass, so she ventured into the same garden where she had met the Duke of Bedford the night before. She thought it might help to clear her thoughts. She didn’t know Sister Claire was following right behind her. Instead, MaryAnn spotted a coif of curly, light brown hair and felt her heart give a silly little hiccup—the Duke of Bedford was still here!

Hastening her steps, she approached him, and his head swiveled around to meet her. This time, she saw the true depths of his eyes, a light, heavenly blue, as pure as the sky above them. He was dressed in a dark-blue coat with matching breeches and a waistcoat of cream silk brocade. His cravat was slightly crooked. She wanted to reach out and stroke her fingers over the satiny fabric, but she felt appalled at the egregious urge.

“Good morning—” she said, and as she was about to add his title, Sister Claire came to her side.

“Have you met His Grace, MaryAnn?” Sister Claire asked affably.

She did not want to lie, but she couldn’t tell the nun that she had been out of bed last night either. “We met briefly.”

“Ah,” Sister Claire nodded.

Meeting MaryAnn’s eyes, the Duke of Bedford gave her a small knowing—and conspiratorial smile—while she took a seat opposite him. Sister Claire sat nearby as they began to converse.

“I hope you found your night a pleasant one, Your Grace,” Sister Claire said. “I know we do not have the comforts you might be used to, but I hope you rested well.”

Adam waved her words off, “My night was wonderful, Sister Claire. I have no complaints at all. As a matter of fact, your simple living proved to me that the lavish things we sometime surround ourselves with neither increase nor remove what is most important. And thank you for sending a morning meal to me, and my coachman as well.”

“It is our pleasure, and I am glad you had a restful night,” the nun replied. “I suppose you will be off to your home this morning?”

“I may leave soon,” he replied just as the bell toll for morning mass resounded in the air. “But I find myself with many questions about this place.”

“Such as what, Your Grace?” MaryAnn asked.

“How is the schooling here?” he asked. “What do you learn?”

He must be thinking about the conversation we had last night when I told him I did not want to leave this place.

“We study French, Latin, simple arithmetic, and drawing,” MaryAnn replied. “Sometimes we study Greek and Italian, while we also have elocution, needlework, and singing, and music. Sundays are mostly for church and washing our clothes.”

His brows lifted high. “Those subjects are comparable to those I learned at Cambridge. I do admire the effort the Sisters make in ensuring the young ladies are fit for life beyond this convent. Most of the ladies I know only find satisfaction in gaining a new spring wardrobe.”

Sister Claire beamed. “We know it’s not a traditional education for ladies, but we believe playing the pianoforte and being fluent in languages is not only the pinnacle of being accomplished. We teach daughters of merchants who are not able to live the luxurious life of the ton. They typically go on to be governess and chaperones. We must equip them too.”

“I see.” He nodded. “And what is life here like for you, Sister Claire?”

While Sister Claire expounded on her routine of waking before dawn for prayer, teaching school in the daytime, and reading Vespers at five, MaryAnn silently watched the Duke of Bedford. He was not an expressive man, but emotions flittered across his face now and then.

He truly is handsome, but troubled. I wonder why?

As Sister Claire expounded on life in the convent, the Duke of Bedford’s hand kept running up and down his thigh, and more than once or twice, she saw him lift his hand but instantly drop it back in place. Why?

He drew a silver timepiece from his waistcoat pocket and rubbed the casing against the leg of his breeches. Examining it, he sighed then stood. “I do thank you and the Mother Superior for giving me shelter, but I am afraid I must go. I have a long journey to London ahead of me.”

“Oh, my,” Sister Claire said, wringing her hands. “I was just about to ask you to stay for luncheon.”

He gave her a wry smile. “As much as I would love to stay, I must go. It will take me a while to get to Mayfair, and I have some important stops to make on the way.”

Thinking about it, MaryAnn realized he must live near her parents, but then again, many of the ton lived in that upscale neighborhood.

Standing, she smiled. “I wish you a safe journey, Your Grace.”

He bowed. “Thank you, Lady MaryAnn. Sister Claire, will you please see me off?”

Trailing behind them, MaryAnn watched as he mounted a black-lacquered carriage with a gold seal of a circle of laurel leaves and an anchor in its middle. He boarded the carriage. Through the window, she saw how he sat and pressed the heels of his hands to his eyes. MaryAnn was sure he had not realized he’d done it, since once the carriage began moving, his hands remained at his eyes.

“What a lovely young man,” Sister Claire said. “I doubt I have seen such a gracious, sensible, humble lord before.”

Thinking of his advice to follow her heart, MaryAnn nodded. “I see it as well.”

“How was your interaction with His Grace long enough that he knew how to address you?” Sister Claire asked, pointedly.

Thrown by the question, MaryAnn could only nod, then add, “I . . . erm, saw him and wondered what he was doing here. He told me his name, and I told him mine. He explained that he had asked for a room after a long journey, and I took him at his word.”

MaryAnn was painfully aware that she had left out the truth about when they had met and where, but she hoped Sister Claire would take her at her word. Judging from the accepting look on the nun’s face, she had.

“Were you afraid you would get in trouble for speaking to him?” Sister Claire asked as they headed to the doorway to lead them to the dormitories upstairs.

“A little, yes,” MaryAnn replied sheepishly. “I mean, how often do we have lords of the realm visiting here?”

“I understand,” Sister Clair nodded sagely. “But you should not fear, dear MaryAnn. You are free to speak to anyone you please. Remember, we do not allow just anyone to walk through our doors, and if we do allow someone of questionable character, that person is kept apart from you girls.”

“I know,” MaryAnn replied. She made to head through the doors when another nun came hurrying towards them. MaryAnn’s stomach sank, for she believed she knew why the nun was rushing towards her.

“Sister Clarence?” Sister Claire blinked. “What is the hurry.”

“My apologies, Sister Claire,” Sister Clarence, a novitiate of the order, bowed her white-covered head. “Miss MaryAnn’s parents are here to see her. They are seated in the small annex room in the chapel.”

“Thank you, that’s wonderful.” Sister Claire smiled, then turned to MaryAnn. “Off you go, dear.”

Nodding, MaryAnn headed to the school’s small chapel, a stone edifice with wooden pews and an altar. She entered the hallowed space, briefly brushing her fingers over the small statue of Mary holding baby Jesus, and then headed to the small room beyond a corridor.

As she entered, her mother stood and rushed to her, enveloping MaryAnn in her embrace. Small and petite, her mother, Harriet, did not look her age. At eight-and-forty, her mother still carried a youthful face and spirit.

“Oh, dear heart,” Harriet sighed in relief. “I am so glad to see you.”

When she pulled away, MaryAnn spotted tears at the corners of her mother’s eyes and felt her heart twist. Kissing her mother’s cheek, MaryAnn stepped away and took in the dress her mother was wearing.

Cut in the latest fashion, her mother’s silk gown gathered under the bosom and fell in a soft, graceful column to her slippers. Delicate puffed sleeves bared most of her shoulders, and the neckline was trimmed with tiny silver tassels that matched the silver coronet nesting in her mahogany locks.

Touched by her mother’s emotion, MaryAnn replied, “I’ve missed you too, Mother. Please don’t cry. I’m here now.”

Harriet dabbed the back of her hand to her eyes. “I know, darling. Its only that you’ve been here since last Christmas, and now its Advent. Your absence has made its mark on our home.”

While resting her hands on her mother’s shoulders, MaryAnn looked over to her father, who was standing silently by. Timothy Hills, Earl of Chesterfield, wore his customary unembellished black, and the austerity of his jacket emphasized the width of his shoulders and his tall stature, down to where his trousers were tucked into gleaming Hessians. He had silver patches at his temples and a little more pouch to his stomach than she remembered, but he still easily commanded the room.

Pulling away from her mother, MaryAnn went to embrace him, and felt happy at the small curve of his lips. “Good morning, Father. How are you?”

“Much better now that I am seeing you, darling,” he replied. “My, you’ve grown.”

Laughing, MaryAnn peeled away from him, and they went to sit at one of the many padded seats in the room. A bit nervous at what she knew was coming, MaryAnn picked at her skirts. “How have you been?”

“Dreadfully bland without you at home,” her mother said. “It’s not satisfactory to have tea with a long-haired Persian cat who is more interested in sunning itself in the window than engaging with you.”

“I suppose Queen Sheba is the same as always, then.” MaryAnn laughed at the memory of the cat her mother had gotten years ago. “Disinterested in anything but what she wants.”

“Very much so,” Harriet’s eyes traced MaryAnn’s face incessantly, as if she wanted to remember her daughter’s likeness in case MaryAnn refused to go back to London with them.

“And you, darling?” her mother asked. “How are you faring?”

Swallowing, MaryAnn replied, “I’m doing well here, I’m happy, and my studies are going well.”

“Your mother has a flair for the dramatic,” Timothy snorted. “It is not ‘dreadfully bland’ at home, but while everything has been fine, MaryAnn, your absence has been noted. It has continued for too long. I know you’ve found a connection with the people here, darling, but its high time you returned home. It is why we’ve come.”

While she had been forewarned, MaryAnn heart still sank. She supposed a part of her had been hoping her parents would have dropped the issue, but, clearly, they had not. Taking a deep breath, she said, “But I feel much better here.”

Her words sounded weak to her ears, and MaryAnn cringed inwardly.

“I know you do, but I assure you, you’ll be much happier and will learn much more at home with us,” Timothy said. “And it is time for you to be introduced to Society, dear. It should have been done two years ago when you were ten-and-six, but we felt you were not ready. Now, we believe you are. You’ll have liberty, love, and find new friendships as well.”

Her stomach roiled with nervousness. For the past few months, she had gone over ways to tell her parents she wanted to become a nun and pledge her life to the church, but she had always been too scared to do it for real. Now, she had the chance. As she opened her mouth to speak, Sister Claire walked into the room.

“Lord and Lady Chesterfield,” Sister Claire bowed her head. “Good to see you again.”

“Same to you, Sister Claire.” Her father stood and bowed. “Thank you for playing your part in molding MaryAnn into the lady she has become and giving her an education. I ask that you now allow us to take her home, as it is time for her to be introduced to Society.”

Sister Claire’s surprised gaze shot to MaryAnn, who was sitting stock-still in the chair. While shivering with nerves, MaryAnn knew it was time to tell her parents what she wanted for her life. Standing, she swallowed and said, “Father, I know you want me to be introduced to Society, but I am happy here, and after my birthday, I want to stay here and take the vows to become a nun.”

Her mother gasped while her father’s eyebrows lowered. “That is absurd, MaryAnn. We did not send you here to become a nun. We sent you here so you would receive an education and grow into a humble lady, not one of the selfish, self-minded ladies who overpopulate the ton.”

“And it’s our family tradition,” Harriet added. “I was educated here, and so was my mother. Neither of us became nuns.”

“Mother, I prefer the simple life,” MaryAnn said more strongly. “I know I will thrive here more than I will at home. I do not need the silks and satins other ladies require to feel comfortable.”

Her father’s lips ticked down. “MaryAnn, this is not a negotiation. You are coming home with us. There is no room for compromise.”

She made to object again, but Sister Claire rested her hand on MaryAnn’s arm. Turning to her mentor, MaryAnn saw what she had hoped not to see on Sister Claire’s face—agreement. “MaryAnn, I think your parents are right. We have had a wonderful time getting to know you, and we will treasure the memories, but it is time for you to go home and embark on this new chapter in your life.”

MaryAnn felt stricken. Turning to look at her father, whose expression allowed no grounds for disobedience, and at her mother, who was a few breaths away from dissolving into tears, MaryAnn felt trapped—and heartbroken. She did not want to disappoint her parents and shatter her mother’s heart. Struggling with the decision, she eventually sighed and gave in.

“I’m sorry. I’ll go home,” she replied quietly, hoping that one day they would understand why she wanted to stay at the convent. Going to her mother, she hugged her tightly. “I’ve decided to come home, but I ask you to give me time to decide if I want to return to the convent after I come of age.”

Her mother looked to her Timothy and then back to MaryAnn. “That’s fine, dear, but I think you might change your mind with time.”

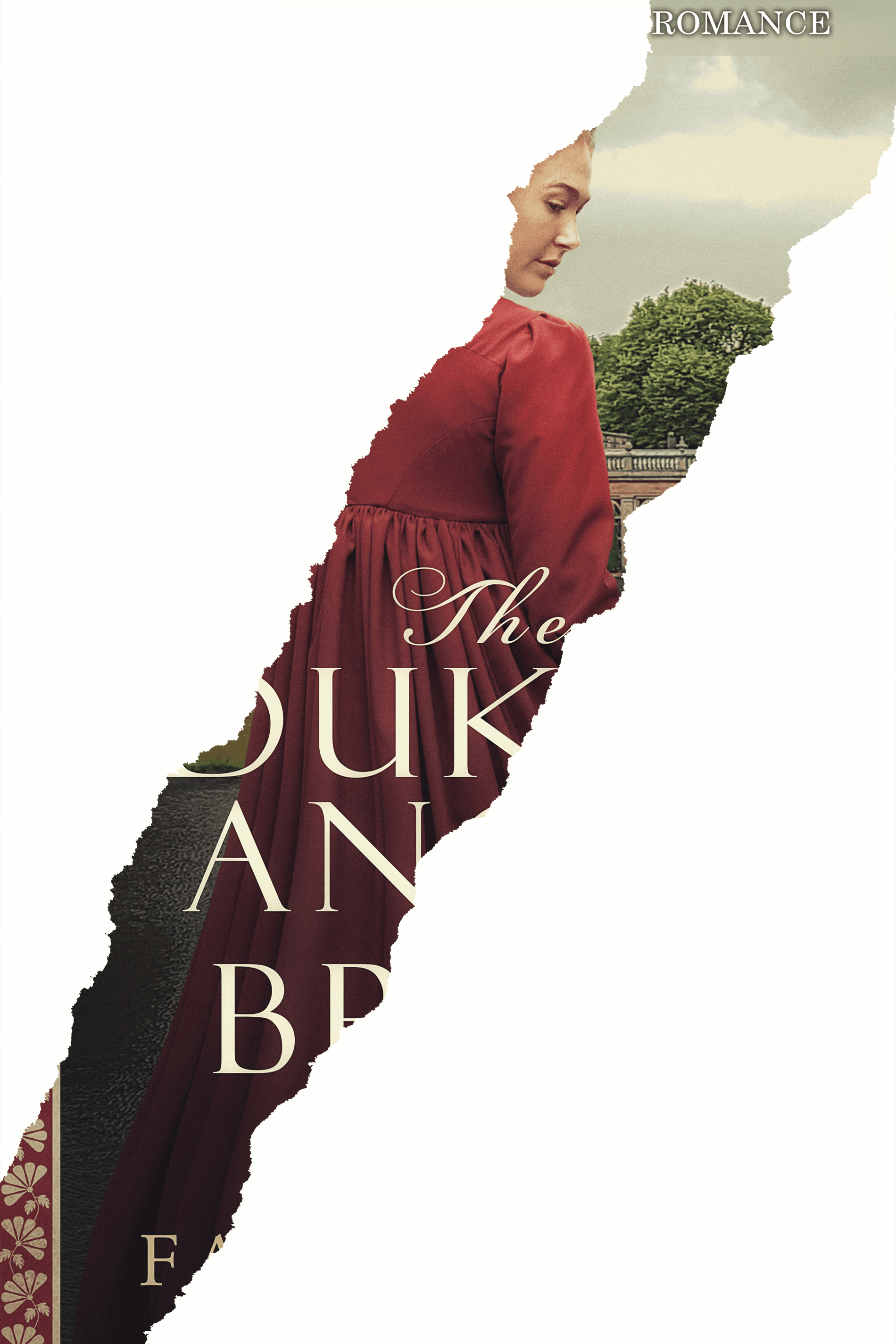

My New Novel is now Live on Amazon!